The landscape of oral cancer is changing in Australia, and dentists are in a unique position to be able to help identify it and initiate an essential early treatment cycle; we asked some medical experts for their advice for our members on how we can best start our patients on the road to recovery.

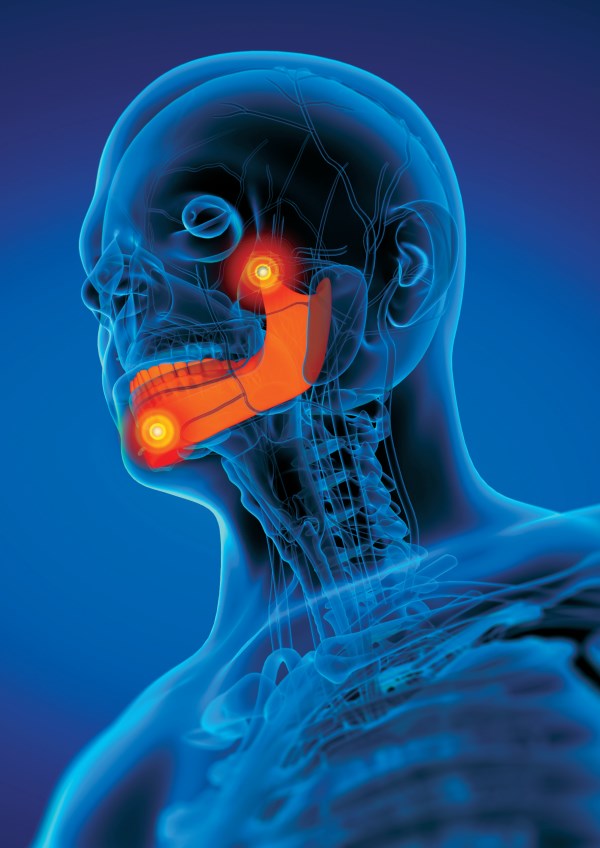

Few people would ever think to present themselves to their doctor for a periodic check of their head and neck, but many turn up to their dentists on a regular basis for an oral health check-up. Associate Professor Bruce Ashford, a head and neck cancer surgeon and cancer researcher at the University of Wollongong, and co-founder and director of Head and Neck Cancer Australia, says this puts us in a strong position to aid early diagnosis of oral cancer – which may include lymphoma, salivary gland neoplasms, bone tumours, etc., although more than 90% of oral cancers are squamous cell carcinomas.

“We rely heavily on the expertise and oral cancer screening of dentists to identify at-risk groups, and to identify disease at the earliest possible stage,” he says. “Dentists are well placed to assess oral cavity mucosal disease as well as lymphadenopathy and to provide sensible advice to their patients about risk-factor modification.

“Head and Neck Cancer Australia recently received a Federal Government grant to develop a learning resource to support dentists by reinforcing the red flags of head and neck cancer and improving their knowledge of bestpractice investigations for diagnosis and optimal referral pathways, and we are looking forward to working in collaboration with the ADA and its members to develop this resource.”

Dr Brian Stein, oncologist at Adelaide’s Icon Cancer Centre, agrees that even dentists who may not be completely confident with advanced cancer screening modalities, can still spot tell-tale lifestyle indicators and perform some important primary checks: “If you have a patient who is at significant risk, because they have a history of significant smoking or drinking, just have a scan of the mucosal lining of the mouth, look under the tongue – all those sorts of things. It takes about 20 seconds, and if you see something, well then that’s quite important. Of course, if you’ve got somebody who’s previously had an oral cancer treated, then they absolutely should be checked like that as a matter of routine. An experienced dentist can have a once-over across the lining of the oral cavity in a minute.

“I think that a lot of dentists are pretty well aware of what to look for in terms of particularly oral cancer, which is what they are going to see the most. Probably the other thing that dentists are also associated with is after-treatment: a lot of patients will have significant issues with dental complications of treatment and they’ll be seeing dentists pretty regularly, so monitoring for any signs of recurrence of cancer is the other issue that dentists can be involved in. I think as a general rule, dental folk are pretty well tuned into concern about oral cancer particularly.”

THE CHANGING LANDSCAPE

“Unlike our medical colleagues,” says A/Prof. Ashford, “I think dentists are extremely well versed in mucosal assessment of the oral cavity. The only detail worth remembering is that oral cancer can affect people at any age, and that a mucosal lesion of concern needs a tissue diagnosis for diagnosis.”

Indeed, while we imagine the cohort most at risk of head and neck cancer may be principally our ageing population, there are surprising statistics that report a worrying trend.

“More young people are developing oral cancer than before and, while the majority of cases occur in smokers older than 45, there has certainly been a rise in oral cancer incidence in particularly young women,” says A/Prof. Ashford. “The rate of oral cancer is increasing and we still see patients present with very advanced disease.”

A web report from Cancer Australia last year compared the case numbers from 2017 – 4,489 new cases of head and neck cancer (including lip) diagnosed in Australia (3,355 males and 1,134 females), with the 2021 estimate of 5,104 new cases of head and neck cancer (including lip) diagnosed in Australia (3,755 males and 1,349 females). In 2021, it was estimated that a person has a 1 in 58 (or 1.7%) risk of being diagnosed with head and neck cancer (including lip) by the age of 85 (1 in 39 or 2.6% for males and 1 in 114 or 0.87% for females).

With these numbers in mind, Dr Stein urges dentists to look beyond their own hesitancies and understand the important role they can play in detection of occurrence and recurrence, while keeping in mind the boundaries of causing further issues.

“I think the problem is that there’s a lot of devil in the detail,” he says. “I suspect probably a lot of people carry in their head some teaching from dental school, or perhaps a course, which basically says if somebody has had a whole lot of radiotherapy, don’t mess around with their teeth too much because you could do bad things to them. I think the issue there is that ill-advised dental treatment, particularly extractions, can precipitate a condition called osteoradionecrosis, and certainly that’s bad – a morbid condition that can be very difficult to manage. If you’re seeing somebody years down the track from their treatment, however, and the person needs a clean and scale, you are unlikely to do harmful things to them. They’re not made out of porcelain.

“You can also keep in mind, if you have a patient in that circumstance and you’re concerned, you can always get in touch with their radiation therapists, their surgeons and medical oncologist, if they have one, and say, ‘I think he or she needs an extraction of this tooth. Is that okay?’ They can then advise, for example, whether the patient was in the high-dose radiation unit area, so you should be getting an oral surgeon involved, or whether it’s not going to be an issue. If you want to do a root canal in a tooth that’s well away from the radiation field, the answer will probably be: ‘Yeah, knock yourself out.’ But if you want to pull out a molar right in the peak radiation area, you may get the answer: ‘Maybe not.’

“Patients recovering or in surveillance following oral cancer treatment are challenging,” says A/Prof. Ashford. “They have potentially had substantial surgery and radiotherapy, all with the effect of making the oral cavity more hostile. Ironically these patients, who are complex, have the greatest need for effective preventive care and maintenance of oral health. I think part of the hesitancy of dental professionals for these patients may be due to feeling out of the loop of their care, which is the fault of their cancer teams. We need to do a better job in communicating treatment and management for our shared patients so that our dental colleagues are empowered to provide optimum care for these people.

“Patients with unstable mucosa and risk factors should be regularly seen,” he continues. “Dentists should feel comfortable engaging with head and neck surgeons if they are concerned about any patients. In our practice, we have many dentists who will email a photo really just to discuss a case. This should be routine and dentists should understand the vital role they play in oral cancer surveillance. We also have a substantial amount of freely available information on the website of Head and Neck Cancer Australia (headandneckcancer.org.au).”

COLLABORATION AND COMMUNICATION

“If a dentist sees something that they’re quite concerned is not just a cancer precursor but a substantive malignancy, I would expect them to get on the phone,” says Dr Stein. “I think the head and neck fraternity are pretty good in terms of fitting people in as a matter of urgency. If a dentist called one of my surgical colleagues and said, ‘I’ve got a patient here who’s got an ulcer, and I’m concerned it’s malignant’, I would be very surprised if that person does not get fitted in pretty quickly.”

Collaborating in delivering a systematic treatment plan is also essential when dealing with patients about to embark on radiation therapy or other cancer-related medical procedures.

“Certainly, patients who are having head and neck cancer treatment will be assessed,” says Dr Stein. “It’s standard operating procedure that they get a proper dental assessment, usually from a specialised unit. But a much more common situation would be the patient who is being set up to have chemotherapy, or some of the boneprotecting drugs that have dental implications, and we want the patients to be dentally fit.

“There are two things that need focus in this kind of case. One is prophylaxis against loss – for people who’ve had head and neck cancer treatment and have had significant changes in saliva, they and their dentist are going to become on first-name terms. It really is important to motivate people to have regular treatment because they are really at risk of accelerated decay. Preventing that is the best possible outcome.

“The other thing is dental rehabilitation, which can be tricky as it depends a lot on the quality of the bone, and how much radiation has been given, so collaboration and communication is paramount.

“Head and neck cancer is the cancer par excellence, where multidisciplinary treatment is super important, and has made a significant difference to patients. As a rule, we would like to encourage a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach as the standard of care.

“With oral cancer, a significant number of recurrences will occur in the place where the cancer originally was in the mouth, plus the vast majority of people who recur, do so on the basis of symptoms or signs. You don’t need a special scan; with the vast majority of people, you should be suspicious of recurrence because the patient has pain, ulceration, or significant changes.

“Even outside of recurrence, dentists will often be managing treatment-related problems in the mouth – that won’t necessarily be during the acute treatment, but certainly late effects, collateral damage is very much the case. Particularly with the systemic treatments, there is the need for prophylaxis when there are complications from treatment, such as accelerated decay.

“Bone-strengthening treatment is pretty much mandatory for people who are having chemotherapy, for example, and this can be an issue because sometimes you don’t have the time available to do this. But having somebody who is dentally fit can reduce risk of infective complications. So that’s something very useful that dentists can offer their patients. Whilst a dentist may not be a formal part of the head and neck cancer team, they are crucially important as a contributor to the patient’s care.”

THE ROLE PLAYED BY TECHNOLOGY

Dr Anastasia Georgiou, an oral medicine specialist and past president of the Oral Medicine Academy of Australasia, says that technology can assist with the timely diagnosis and treatment of oral cancer – from the newest laser scanning to the humble smartphone.

Digital technologies can expedite appropriate referrals, assist with triaging patients to be seen and also guide where to take a biopsy from. Digital technology also has a role in screening for oral cancer. Simple digital technology, such as a smartphone or digital camera, enables an image of a suspicious lesion to facilitate an expedited referral with prompt assessment by a specialist and prevent delay in diagnosis of oral cancer. Clinicians who take images of oral lesions for follow-up can document lesion progression over time. It also improves communication and access to care for patients who live remotely. Patient outcomes are improved by early diagnosis.

Advances in technology with adjunct fluorescence-based tools can enhance visualisation of mucosal abnormalities but must be used by a well-trained clinician to interpret the results and manage appropriately.

New collaborative research with the Melbourne University Dental School and Optiscan uses confocal laser endomicroscopy for diagnosis of cancerous tissue in real time and mapping the patient’s mouth to monitor for change, to enable early diagnosis.

I hope that oral cancer awareness and screening is adopted as part of an annual dental check-up for every patient and that medical doctors are trained in the assessment of the oral cavity. Early diagnosis is the key to improving patient outcomes with oral cancer. Advances in technology are set to enable a ‘mouth map’, similar to Mole Map, for patients to identify early disease. There are also developments in identification of prognostic markers to reliably identify which potentially malignant lesions will undergo malignant transformation.

Associate Professor Ramesh Balasubramaniam OAM is an oral medicine specialist and immediate past president of the Oral Medicine Academy of Australasia, who has lectured in the areas of orofacial pain, oral diseases and dental sleep medicine. He is at the forefront of digital innovation that helps Australians better access oral medicine specialists.

There are two tools we have developed to solve the issues of access to care in oral medicine, including early diagnosis of oral cancers.

1. OralMedMate is a phone app which serves as an interactive clinical tool to assist clinicians in formulating differential diagnoses by filtering diseases/conditions based on the patient’s history and clinical features. You can search for a disease, read concise summaries and view clinical images. Also you can generate a referral via the app to an oral medicine specialist in Australia.

2. TeleOralMedicine (teleoralmed.com.au) is a convenient, easy-to-use online service for all Australians who need oral medicine services, especially those living in remote areas or aged care facilities and do not have easy access to specialised oral medicine services. A clinician can organise a referral and upload clinical photos they have obtained of the patient’s disease, etc.

Once the referral is sent, the TeleOralMedicine staff will invite the patients to schedule a virtual consultation via telehealth.

SOURCE:-